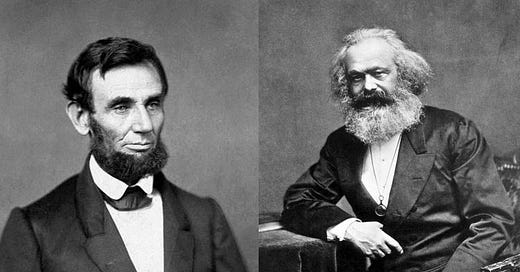

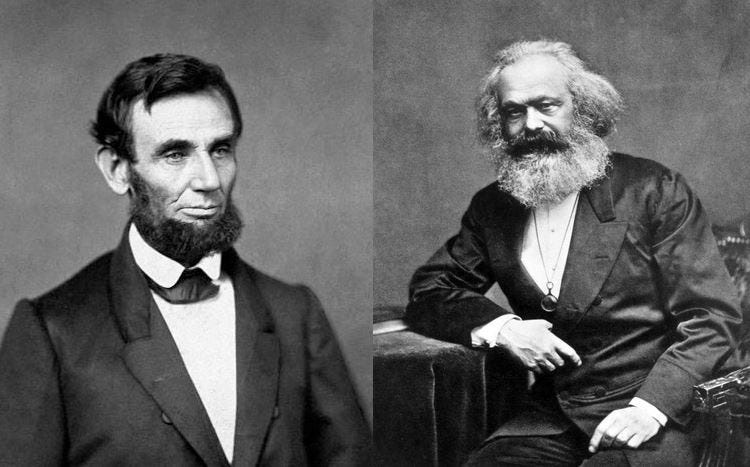

Awhile ago, my husband and I were discussing my dissertation piece on Marxism and U.S. history in the back of a New York City cab. The cab driver was listening and interjected that he had been working on his PhD on this very topic and said Lincoln and Marx were “pen pals.” Fascinated by this revelation, I later researched the topic and found that indeed, they had corresponded. Marx’s influence on Lincoln is the subject of much debate.

Marx was published in a New York newspaper read by Lincoln and, he had written Lincoln directly who sent a detailed acknowledgement back to Marx. Lincoln does not credit Marx with his influence but his own words at times echoed Marx. There is no record of the two meeting in person. No one believes that Lincoln was a Marxist but, there may be some common ground beneath the general perception of the label. Because of Marx’s political views, many people do not want to believe that Lincoln was able to extract any philosophical beliefs from Marx. Therefore, their connection is history not taught.

Historian and author, Robin Blackburn, wrote about the Marx and Lincoln connection in his book “An Unfinished Revolution.” Blackburn believes their relationship led not to a workers’ revolution, but to a revolution for democracy. The following information is primarily based on Blackburn’s research and indicates what we know for sure and what may be surmised.

Across the Pond, Marx and Friedrich Engels published “The Communist Manifesto” in 1848. This period saw a surge of German immigrants to the U.S. who were working in the industrial area and who were also anti-slavery. Marx had allegedly considered moving to Texas himself and in 1843, applied to the mayor of Trier, his birthplace, for an immigration permit.

Marx began writing regularly for the New York Tribune in 1852, a newspaper managed by an American socialist named Charles A. Dana. He was a prolific writer, producing almost 500 articles with eighty-four of them running on the front page under the paper’s byline instead of his own. These articles later contributed to Marx’s book, “Capital.” As the newspaper of choice for Republicans and read faithfully by Lincoln, one may conclude that it would have been difficult to read the paper without reading Marx, either on the paper’s front page or under his own byline.

Lincoln’s friend, Horace Greeley was a fellow Whig and the founder of the influential New York Tribune which helped establish the 1854 political platform of the Republican Party. Marx’s articles represented anti-slavery views, were radically pro-worker, and promoted wealth distribution of land to the poor and emancipated. Greeley was an opponent of free markets over the working class and saw oppression through labor and slavery.

Marx predicted trouble ahead for the pro-slavery South. He saw Southern slaveholders as parallel to European aristocrats (which they also often saw in themselves). His view was that slavery destroys capitalism by creating less favorable conditions for both Black and white workers. How could paid workers compete with free workers? Marx advocated for organizing labor to help workers stand up to capitalists for better working conditions and pay.

President Lincoln delivered his 7000 words State of the Union draft to the House and Senate in December of 1861. It was published in both Northern and Southern newspapers and was his first communication to the nation since his inaugural address. Lincoln focused his attention on “disloyal citizens” who were resisting the Union, along with the national budget, and the nation’s military strength. His final 800 words (more than 10% of his speech) was on what the Chicago Tribune labeled, “Capital vs. Labor” including the following words:

These words were not attributed to Marx but certainly the message resonates with his philosophy. This raises the debate of Lincoln’s familiarity with Marx. Was he reading Marx and were there unrecorded communications between the two? Some historians posit Lincoln was a faithful reader of Marx but that may be more of an inference than an historical fact. Lincoln was an avid reader. If he found common beliefs with Marx and accepted his direct correspondence out of the many he received and rejected, it is not inconceivable that he regularly followed Marx’s writings. The two were contemporaries (nine years apart), had mutual friends, and appeared to be intellectually and politically interested in each other’s work.

Karl Marx drafted an “Address” delivered to the London-based International Workingmen’s Association that congratulated Lincoln on his reelection in November of 1864. The “Address” highlighted Lincoln’s reelection would be a turning point for nineteenth century politics and declared it a victory for the North. Marx also saw the reelection as affirmation for free labor (free to work anywhere and accept a salary of mutual agreement) and a blow to the slave power capitalists. Lincoln’s British Ambassador, Charles Francis Adams (grandson of John Adams) forwarded the “Address” to Washington to be shared with Congress and the President. The “Address was signed by an assortment of prominent British trade unionists, French socialists, and German social democrats.

When the Civil War began, U.S. newspapers focused on domestic issues. Meanwhile, Marx was writing his support of the Union in European papers. Much of Europe was dependent on the production of slave labor, especially cotton, dividing European support for the Union and for Confederate secession under the premise of self-rule. Marx attacked the hypocrisy of capitalists who said they were anti-slavery and yet, endorsed the South’s position of self-determination. Their counter-response to Marx was that the North was exercising protectionism against the free trade of the South.

Marx continued the writing attacks about these false premises. He made the argument that secession was initiated by the Southern slave owning oligarchs who were feeling politically and economically threatened by the North. As the Northwest expansion only allowed free states, the South felt their power diminishing on the Federal level. The South believed they had no influence with Lincoln, who was elected without their support.

Lincoln met with the New York chapter of the Workingmen’s Association in 1864 and spoke of the strongest bonds including “one uniting all working people, of all nations, and tongues, and kindreds.” which was rather similar to Marx’s slogan, “Workers of the world unite!” While Lincoln did not call himself a socialist, he supported a system of wage labor and though it was different from the one Marx promoted, it was enough to keep socialists as political allies to the Republican Party.

Two facts are viewed as helping Lincoln get elected, former German revolutionaries who were predominate in the Republican Party and the party’s newspaper, The Tribune. German Americans were raised with anti-slavery views and felt so strongly about it, that nearly two hundred thousand German Americans later volunteered for the Union army. Once elected, Lincoln rewarded Dana by making him Assistant Secretary of the War Department to collect information on the performance of the military and its leadership. Other friends of Marx were also strong supporters of the Union and received senior military commissions from Lincoln including Joseph Weydemeyer and August Willich, both former members of the Communist League, who were promoted first to the ranks of Colonel and then to General.

Marx continued to write anti-slavery pieces for The Tribune and Greeley continued to push Lincoln on the subject of emancipation. Lincoln ultimately issued the Emancipation Proclamation on New Year’s Day in 1863. For the following three years, Marx continued his efforts to influence Lincoln that included a letter to him in January of 1865. The letter congratulated Lincoln on his reelection, on behalf of the International Workingmen’s Association which included the politically radical left and the working class. In his letter, Marx claimed the slaveholder oligarchs were staining the republic and just as the Revolutionary War had helped to elevate the middle class, the war against slavery would elevate the working class. A reply acknowledging Lincoln’s receipt of the letter was delivered via Charles Francis Adams.

Lincoln’s reply stated that Marx’s letter was “accepted by him with a sincere and anxious desire that he may be able to prove himself not unworthy of the confidence which has been recently extended to him by his fellow citizens and by so many of the friends of humanity and progress throughout the world.” Adams conveyed that Lincoln considered Marx and company as friends and that Lincoln was encouraged to persevere based on the testimony of Europe’s working class. The letters were published in U.S. and British newspapers to Marx’s delight.

Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln agreed on the cause of “free labor.” Additionally, Lincoln appreciated the support of the German American community and the international communist opposition to European recognition of the Confederacy. The Working Men’s Association embraced many of communism’s platform, including the limit to an eight-hour workday which attracted thousands of workers to their ranks. Unions appealed to workers of all races including Blacks, whites, Indigenous, and immigrants, as well as men and women. Marx and the unions were responsible for exposing the capitalist robber barons for their greed and exploitation and inspired strikes and class rebellion by the workers.

Lincoln supported the concept of “free labor” because he believed that workers could elevate themselves into positions of management, ownership, and as an employer. Marx believed that this was an unrealistic belief because few workers managed to move up in position. He saw the worker as only partially free because he was selling his labor to another while supporting his family and was unable to choose his labor at will.

Lincoln’s position on slavery is also controversial as he did not believe that Blacks and whites could or should live together. It was Lincoln’s desire to free the slaves and emigrate them to colonies in the Caribbean or Africa. Like Marx, who focused on worker related issues with slavery and not morality, both viewed free Blacks as a threat to white workers because they were perceived to be willing to work for lower wages and therefore would be hired over white workers. This will be the subject of a future article.

References and recommended readings:

Hear the address Marx drafted to Lincoln for his 1865 re-election read aloud at the top of the post, and read it yourself here.

https://www.amazon.com/Unfinished-Revolution-Karl-Abraham-Lincoln/dp/1844677222