Chinese Prostitutes in 19th Century California

Kidnapped and imported to serve white capitalist needs

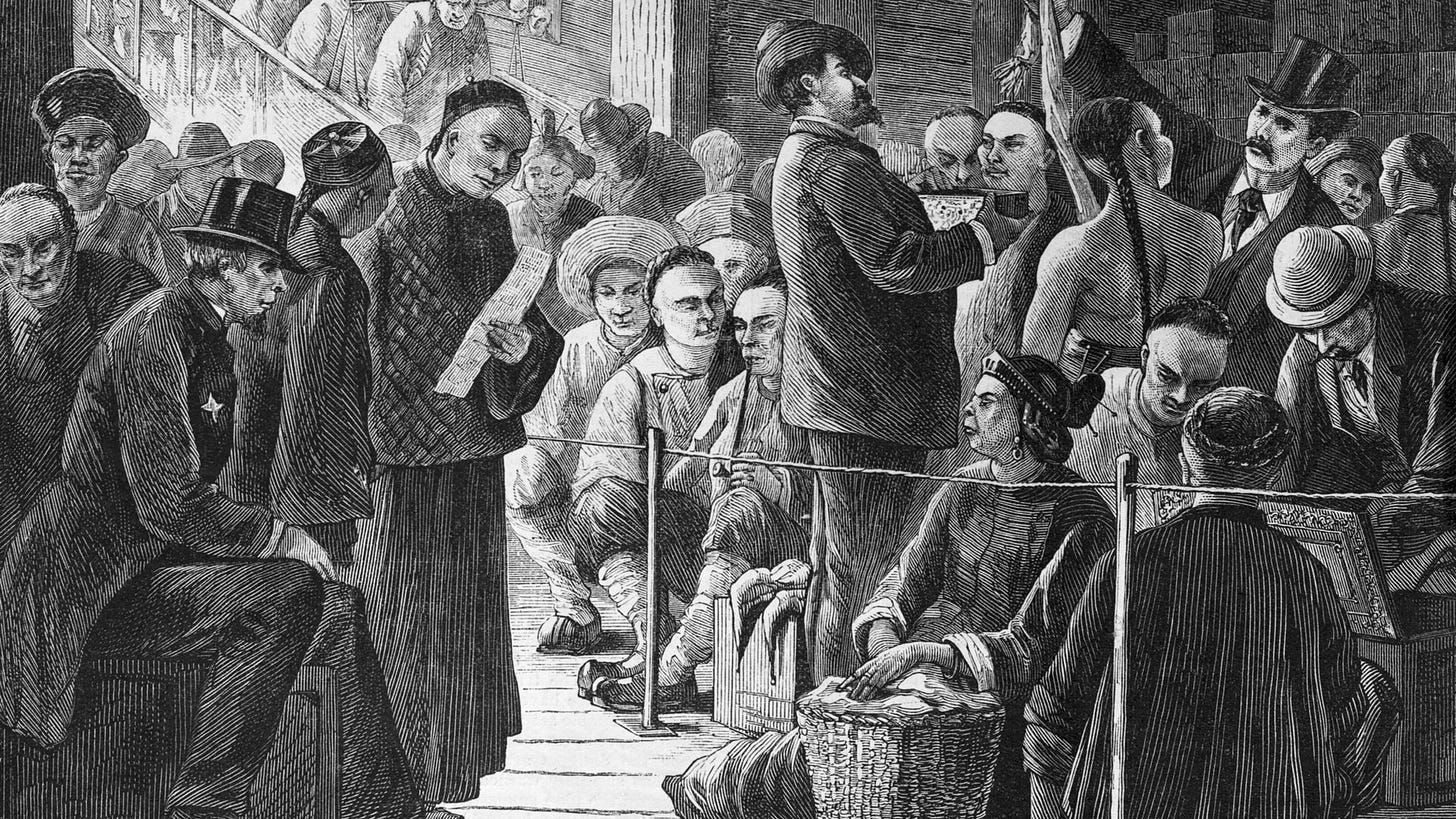

Asian immigration was one of the greatest contributors to urban growth in the nineteenth century. Chinese immigrants began arriving in the U.S. shortly after California’s gold discovery in the 1850s. Nineteenth century Chinese immigrants were encouraged to immigrate to America’s West Coast due to a growing white capitalist need for short-term cheap labor to work the land and build infrastructure. West Coast development was important for white capitalists to compete politically, economically, and socially with the East Coast. Low wages paid to solo immigrating Chinese men assured they would not set up permanent residency with their families back in China. A collaborative effort in America by Chinese and white men in the mid-nineteenth century included the importation of kidnapped and purchased Chinese girls and women for enslaved Chinese prostitution. This effort was to address the issue of lonely Chinese men to maintain a low-wage laborer supply while their families were still in China.

A lack of Chinese women immigration was primarily due to limited financial resources and the difficulties of living in the American West. The 1875 Page Act was a deterrent for Asian women immigrants under the presumption by white Americans that Chinese women would pursue the profession of prostitution. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act restricted the number of Chinese male laborer immigrants and only allowed the daughters and wives of Chinese merchants or native-born Chinese to immigrate. Over ninety percent of the Chinese immigrants between 1860 and 1910 were male.

This dearth of women gave rise to Chinese tongs or secret societies that imported Chinese women for prostitution to service both Chinese and white laborers. One tong imported 600 women for prostitution in 1854 while another brought in 6,000 women between 1852 and 1873. The 1860 San Francisco census documents ninety-six percent of “working” Chinese women were prostitutes (excluding girls under the age of twelve and women in male headed households). This statistic reflected that Chinese women were brought to this country for a singular capitalist purpose.

Chinese women were viewed by many whites as disposable, disease carrying, immoral home wreckers and a threat to white women, men, and children and ultimately, to societal whiteness. Chinese prostitutes were specifically enslaved by their exploiters to serve the overall white capitalists’ need to maintain a cheap Chinese male labor workforce. When services were no longer needed from these girls and women, they were dehumanization and exiled from white communities.

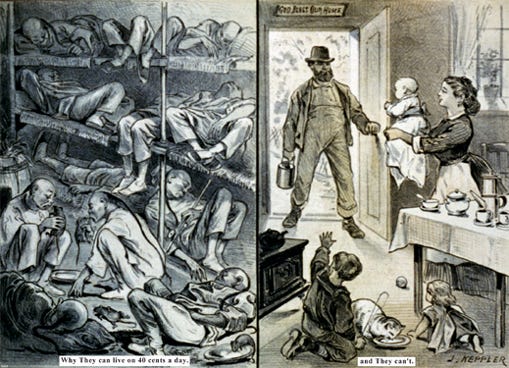

Urban populations swelled in the late nineteenth century from the influx of cheap Chinese immigrant labor. The increasing number of Chinese immigrants created white apprehension, especially in the labor market. The late 1860s brought an economic depression that pushed thousands of white laborers into unemployment. White laborers found Chinese workers an easy scapegoat for their situation rather than blaming the white capitalists who hired them.

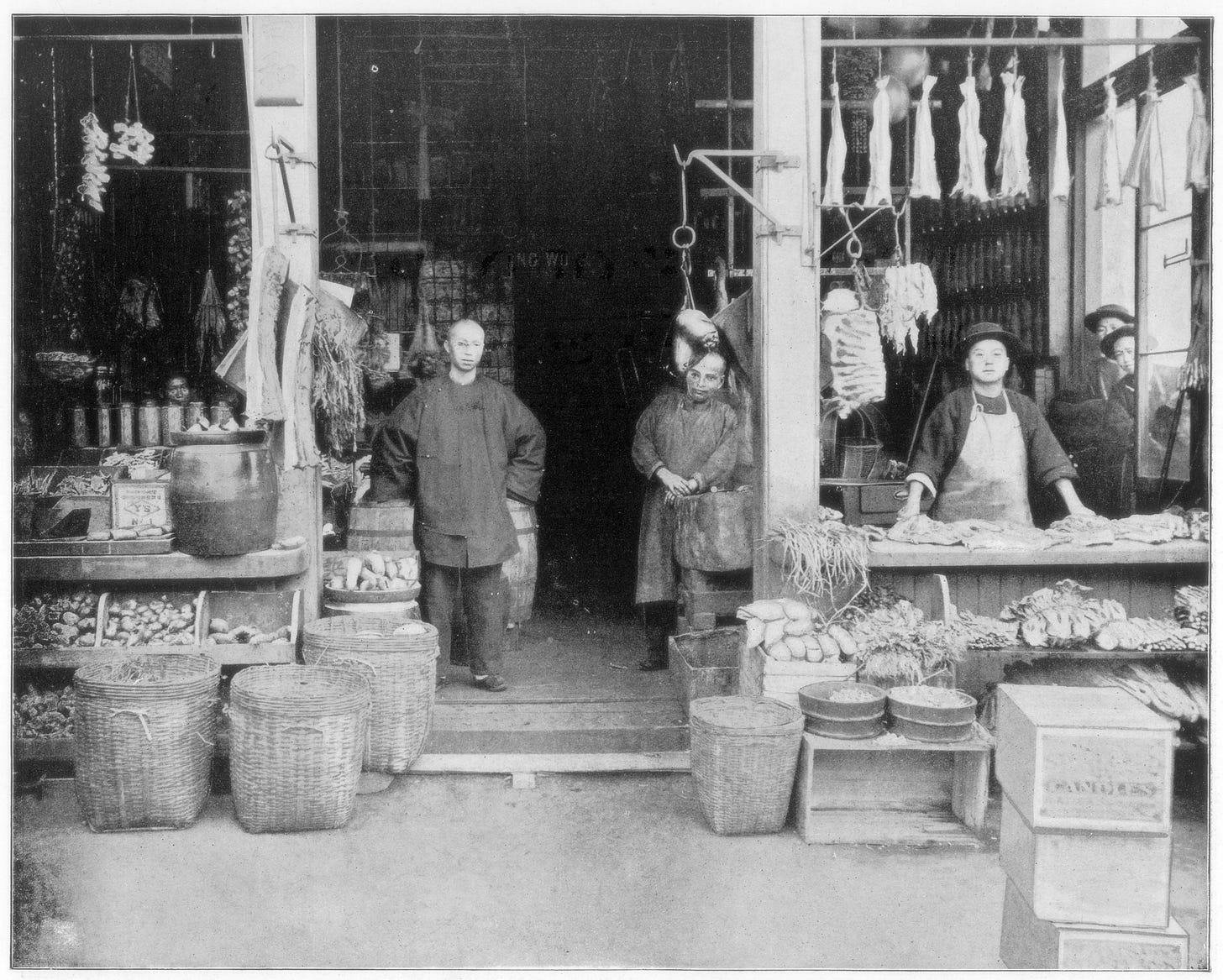

Chinese populations grew in an area referred to as “Chinatown.” These condensed urban areas bred white contentment and racial discrimination that was disseminated through travelogues, journalists, government agencies, and fiction. California Chinese immigrants were the victims of anti-Chinese sentiment while serving white American capitalists needs for cheap labor.

White outrage over Chinese immigrants provoked riots across the country. Many Chinese immigrants migrated to California when driven out of other areas. Chinese land ownership was relatively low. In 1873, only seven percent of San Francisco’s Chinatown was owned by Chinese immigrants, less than a dozen properties. White Chinatown landlords exploited Chinese occupants with high rents, often triple the white rental rate. White middle-class perceptions saw Chinatown as a collective impression of unacceptable cultural, behavior, and living standards serving as proof that the Chinese were incapable of assimilating into white society. Chinatown was portrayed as the “hell” of San Francisco and contrasted against the heaven of whiteness across town. Common descriptions of this perceived hell hole included words like “pen,” “dens,” “coffins” and “dungeons” with subterranean living quarters “fit for animals, criminals, and the dead, not for human habitation.”

The 1877 California Legislature report states, “…we believe, and the researches (sic) of those who have most attentively studied the Chinese character confirm us in the consideration, incapable that the Chinese are of adaptation to our institutions.” Americans viewed Chinese immigrants as “heathen, crafty, and dishonest” sub-humans and a threat to white society. Meanwhile, white industrialists praised Chinese male laborers as a readily available and plentiful cheap resource. While Anti-Chinese sentiment was broadly applied, the enslaved Chinese prostitutes became the focal point when Chinese immigrants were no longer needed.

Widely accepted false claims stated white women workers were unsuccessfully competing with Chinese workers. As a result, white women found themselves unemployed and forced into prostitution. This false belief was perpetuated in the 1877 Report to the California State Senate of its “Special Committee on Chinese Immigration” questioner, concerned about young white girls who asks his witness:

Do you think that they [Chinese laborers] drive servant girls from their places, deprive them of an opportunity of making an honest living?

Yes, Sir.

And has that fact added to the ranks of prostitution?

Yes, Sir

Chinese prostitution on the American western frontier differed from white prostitution. White women capitalized on their independence and welcomed opportunity by running brothels as an employer or by serving as a wage working prostitute. During the peak Gold Rush period, white prostitutes were considered “high class” and charged higher wages. They ran booming profitable business with few white female competitors. Meanwhile, exploitation of Chinese women continued until the twentieth century. California Legislature 1877 testimony reflects white views of Chinese prostitution compared to white prostitution:

The prices are higher, and boys of that age will not take the liberties with white women that they do in Chinatown. In addition to that, it can be said on behalf of the white women that they would not allow boys of ten, eleven, or fourteen years of age to enter their houses. No such cases have ever been reported to the police, while the instances where Chinese women have enticed these youths are very frequent.

It is believed the first prostitute in San Francisco was a twenty-year-old Hong Kong prostitute in 1848 before trafficked Chinese prostitutes became the norm. Early free agent Chinese prostitutes served a predominantly white clientele and earned enough capital to open their own brothels, but few could afford the associated business expenses or had business knowledge. The lack of resources for Chinese women opened the door to Chinese organized criminal societies known as “tongs” by 1854. Tongs controlled kidnappers, importers, and police. They collected “taxes” to buy assistance in the importation and trafficking of Chinese prostitutes.

California Legislature 1877 testimony stated, “It was proved before the committee that Chinese women; in California are bought and sold for prostitution, and are treated worse than dogs; that they are held in a most revolting condition of slavery…They are cruel and indifferent to their sick, sometimes turning them out to die, and the corpses of dead…are sometimes found in the streets by the policemen, where they have been left by their associates at night.”

Attractive Chinese girls would become concubines to the wealthy Chinese men but if they did not meet expectations, their masters could return them to the auction block. Some Chinese prostitutes served their time in high-end brothels, but most wound up in “cribs” that were shacks frequented by sailors, teen boys, day laborers and drunks. Chinese and white men alike, paid less than a half- day’s wages (25 to 50 cents) for their services.

Chinese recruiting agents collected women in China, arranged their passage, and delivered them to American brothels. Hip Yee Tong was the most notorious importer of women between 1852 and 1873. He is credited with the importation of over 6000 females representing 87 percent of all known imported Chinese prostitutes. Hip’s business practices reflect how the white community profited from his exploitation. Twenty-five percent of his buyer fee reportedly went to white policemen. White lawyers profited through collusion with Chinese importers in obtaining habeas corpus decrees to allow the landing of Chinese headed for the brothels. More laws applied restrictions to Chinese immigration increasing avenues for corruption. White American immigration inspectors and interpreters welcomed bribes in exchange for their expediency in processing women.

Chinese prostitutes owed a twenty-five-cent weekly tax and if unpaid, they were subjected to physical abuse, torture, exile, or even death. Tong blackmail was utilized against prostitutes with fees of fifty cents to five dollars collected under the premise of paying off white law enforcement. Many Chinese women tried to escape the brothels to seek refuge at great personal risk. These risks entailed being kidnapped or falsely charged with theft and returned to their owners. White lawyers readily accepted payments to defend these women and then the lawyers returned the escaped prostitutes back to the brothels.

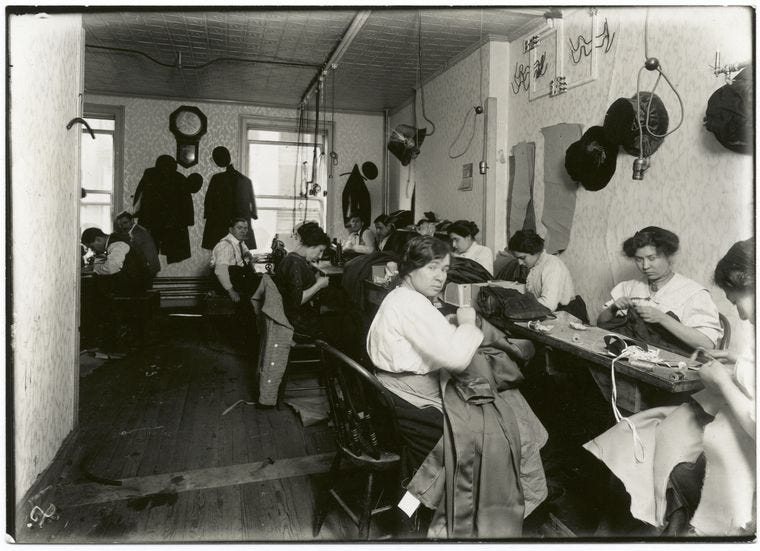

Chinese prostitutes were not just exploited for sexual services as they were often used as daytime semi-skilled laborers. These laboring women were not viewed as victims but as a cause for white female unemployment. The State Legislature 1877 report documents:

During the day these women, as far as practicable, are employed at the various branches of industry as working on shirts, slippers, men's clothing, women's underwear, etc. As this class of operatives do not receive pay for this extra work, it must naturally work a fearful injury to the honest white girl who depends upon her needle for support.”

Chinese immigrants were called immoral and accused of corrupting “the morals of all young creatures.” Their habits and dwellings were seen as extremely filthy which were blamed for creating and spreading fatal epidemics. Whites viewed the Chinese as educating and worshiping in the same way as their ancestors causing their minds and morality to be “immensely lower and inferior condition” to the white race. This analysis was viewed as proof that whites were superior to the Chinese who were seen as barbaric.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the number of Western Chinese prostitutes declined due to several factors including law enforcement, social reformers, and the transfer of prostitutes to other less regulated areas outside of San Francisco. Fewer Chinese families had females to sell or were unwilling to sell them for prostitution in America which created a limited human supply. The influx of white Victorian women and their push for the abolition of prostitution ultimately reduced the number of Chinese prostitutes. Prostitution was legal in California until 1872 when California enacted Penal Code 647 that outlawed prostitution, loitering, begging, public intoxication, drug use, and a host of other "moral" crimes. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act made importation more difficult, thus dramatically increasing the value of prostitutes already in America. Demand for prostitution services decreased with the decentralization of organized prostitution and a more equal ratio of Chinese men and women immigrants. As a result of these changes, Chinese immigrants moved to other low wage stationary production labor for white industrialists.

References

California Legislature. Chinese immigration; Its Social, Moral, and Political Effect. Report to the California state Senate of its Special Committee on Chinese to the California state Senate of its Special Committee on Chinese Immigration. California. Sacramento, F. P. Thompson, Supt. State Printing, 1878. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.32106006093683

Choi, Yoon-Young. “Contested Space of San Francisco Chinatown in Sui Sin Far’s Mrs. Spring Fragrance and Other Writings.” The Journal of English Language and Literature 58, no. 6 (2012): 1023–39. https://doi.org/10.15794/jell.2012.58.6.002.

Fessler, Loren. Chinese in America: Stereotyped past, changing present. New York, NY: Vantage Press, 1983.

Hirata, Lucie Cheng. “Free, Indentured, Enslaved: Chinese Prostitutes in Nineteenth-Century America.” Signs, vol. 5, no. 1, 1979, pp. 3–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173531.

“Immigrant Voices: Discover Immigrant Stories from Angel Island.” AIISFIV.org, n.d. https://www.immigrant-voices.aiisf.org/stories-by-author/1053-jeung-gwai-yings- struggle-from-servitude-to-freedom/.

Iota. The Raid of the Dragons into Eagle-land. A Plague y Pamphlet. San Francisco, Mission mirror job printing office, 1878. https://www.loc.gov/item/19013182/. (primary sources)

Lee, Catherine. “Prostitutes and Picture Brides: Chinese and Japanese Immigration, Settlement, and American Nation-Building, 1870-1920.” eScholarship, University of California, March 13, 2003. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2j56005k.

Lee, Erika. The Making of Asian America: A History. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2021.

Ling, Huping. Surviving on the Gold Mountain: A History of Chinese American Women and Their Lives. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Miller, Stuart Creighton. The unwelcome immigrant: The American image of the Chinese, 1785- 1882. Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1974.

Pierce, Jason E. Making the White Man’s West: Whiteness and the Creation of the American West. University Press of Colorado, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt19jcg63.

Simmons, Alexy. “Red Light Ladies in the American West: Entrepreneurs and Companions.” Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology 7 (1989): 63–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29543241.

“The Oldest Profession.” CSUN University Library, May 5, 2020. https://library.csun.edu/SCA/Peek-in-the- Stacks/prostitution#:~:text=In%201872%2C%20California%20enacted%20Penal,of%20 other%20%22moral%22%20crimes.