Elizabeth Van Lew was born on October 12, 1818, in Richmond, Virginia. Her mother was from Philadelphia and her father was from New York. Working as a hardware salesman, her father became a wealthy merchant who associated with high society while her mother served in a traditional societal role of housewife and hostess at their affluent mansion in Church Hill, Virginia.

Elizabeth attended a Quaker school in Philadelphia, rooting her in abolitionist politics. After having a formal society introduction in Richmond and becoming active in Richmond society, she never married.

Although she and her mother were both anti-slavery, they were still slaveowners who strived to provide independence and financial autonomy to their enslaved. This included allowing their slaves to live and work elsewhere to earn their own income. One of their enslaved was named “Mary Jane” and after being Baptized, she was sponsored and sent on a missionary trip to Liberia between 1855 and 1869 by Van Lew’s parents. The family struggled with maintaining their anti-slavery feelings, social position, and the views of slavery within Virginia at the time. Following the death of her father, her mother emancipated their slaves at the beginning of the Civil War.

When the Civil War began, Elizabeth and her mother required more discretion in their political beliefs. Early in the war, Van Lew and other Richmond Unionists including John Minor Botts, F. W. E. Lohmann, and William S. Rowley, formed an underground network of Union supporters. A Union prisoner of war jail was established on the outskirts of Richmond at an old tobacco factory and became a focal point for this network. Libby Prison was only six blocks from the Van Lew house and was home to hundreds of Union officers. Libby Prison was known for its harsh conditions causing hundreds of Union soldiers to suffer from disease, hunger, and despair.

The Van Lew women sought employment at Libby Prison to serve the imprisoned Union soldiers as “a charitable act”. Van Lew volunteered to become a prison nurse, but her offer was rejected by the prison overseer, Lt. David H. Todd—the half-brother of Mary Todd Lincoln. Van Lew appealed to his superior, Gen. John H. Winder, with flattery and persistence that permitted Van Lew and her mother to bring food, books, and medicine to the Union prisoners.

The Smithsonian Magazine states the Richmond Enquirer wrote, “Two ladies, a mother and a daughter, living on Church Hill, have lately attracted public notice by their assiduous attentions to the Yankee prisoners…. these two women have been expending their opulent means in aiding and giving comfort to the miscreants who have invaded our sacred soil.”

Although Van Lew was never able to gain entrance to the prison, she was able to bribe the guards for various reasons and have prisoners transferred to hospitals where she could have access to them. She would often use a custard dish with a secret compartment for passing information to the prisoners.

This underground work led to a double identity for the women who were passing messages to and from the Union soldiers, providing them extra food and water, and helping them to escape. To try and stifle any suspicions, they regularly hosted public outings for Confederate soldiers and even hosted the prison warden, Captain George C. Gibbs as a boarder in their home. Van Lew was even alleged to have hidden escaped prisoners in her home.

Two Union soldiers who had escaped from Libby Prison with the help of the underground network, told Union Gen. Benjamin Butler about Van Lew. When General Benjamin Butler heard of Van Lew’s efforts in December of 1863, he recruited her to head his Union spy network in Richmond. She developed a network of a dozen Black and white people to spy on the Confederates for the Union, including several of the family’s former slaves. Their former family slave “Mary Jane,” was one of her more prominent spies and traveled under several aliases. The spying went on simultaneously with the work at Libby Prison. Mary Jane (also known as Mary Elizabeth Bowser) even worked as a servant for Jefferson Davis’s family in the Confederate White House as a Union spy.

On January 30, 1864, Van Lew sent her first dispatch to inform Butler that the Confederacy was planning to ship inmates from the overcrowded Libby Prison to Andersonville Prison in Georgia. She provided intelligence on the number of troops he would need to free the prisoners and not to underestimate the Confederates. Butler immediately sent her report to the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, who ordered an unsuccessful raid.

Following the failed raid, a different plan was initiated with better results. On February 14, 1864, over one hundred Union officers successfully dug a tunnel under the street from Libby Prison and escaped. Less than half were recaptured by the Confederates. This improved the morale for the Northern soldiers and further motivated Van Lew to help the remaining Union soldiers in the dismal Richmond prisons, including Belle Isle Prison. After her visit to Belle Isle, she wrote “It surpassed in wretchedness and squalid filth my most vivid imagination. The long lines of forsaken, despairing, hopeless-looking beings, who, within this hollow square, looked upon us, gaunt hunger staring from their sunken eyes.”

On March 1, 1864, Union soldiers once again made an unsuccessful attempt to free Richmond’s prisoners. Unfortunately, the Confederate Army had been warned by a Union soldier on its payroll and successfully prepared for the attack. Twenty-one-year-old Col. Ulric Dahlgren and Brig. Gen. H. Judson Kilpatrick led the raid. Dahlgren, who had lost his right leg at the Battle of Gettysburg, was killed in the raid and most of his men were captured. Dahlgren was hung on display by the railroad depot and later, secretly buried. The Confederates had mutilated his body by removing his wooden leg and the little finger on his left hand. Van Lew was disgusted and promised “to discover the hidden grave and remove his honored dust to friendly care.” Van Lew used her network to discover the burial site, exhumed the body, and buried it in another location. Van Lew had the body returned to the family at the end of the war.

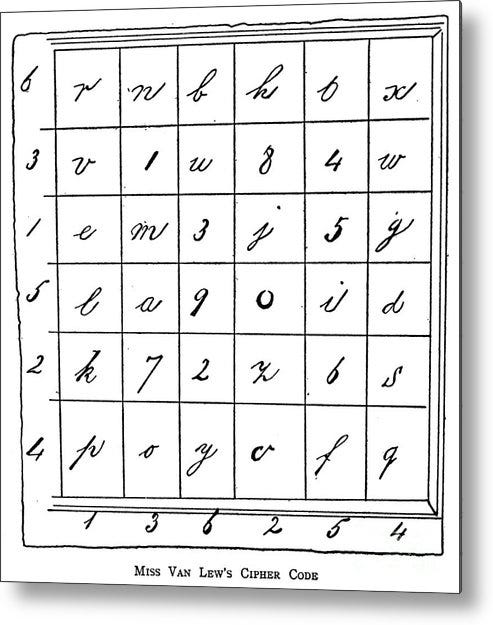

Van Lew, worked with invisible ink and coded messages, and she has been called “the most skilled, innovative, and successful” of all Civil War–era spies. Some speculate that she acted mentally unstable to deflect any suspension of being a spy. Her codename was “Babcock” and she was meticulous in her ability to pass coded messages. Van Lew’s coded dispatches were written with a colorless liquid that turned black when combined with milk. To prevent messages from being discovered, she would tear them into bits and transport them through a variety of couriers and relay stations to get them across the river to General Sharpe's forces. Messages were secured in the soles of shoes and eggshells. If people became suspicious of her activities, it is alleged that she would feign mental unstablity including wandering around Richmond in ragged clothes, muttering to herself, and singing nonsensical songs. General Sharpe reported that the greater portion of the information he received was due to the "intelligence and devotion of Ms. Van Lew."

The Smithsonian Magazine states the Van Lew women faced bullying and threats for their work. “I have had brave men shake their fingers in my face and say terrible things,” she wrote. “We had threats of being driven away, threats of fire, and threats of death.” The Richmond Dispatch wrote that if the Van Lews didn’t stop their efforts, they would be “exposed and dealt with as alien enemies of the country.”

After Richmond fell, Van Lew came to the aid of wounded civilians, regardless of their politics. Following the war, Van Lew received acknowledgement and a small stipend for her effort from General Ulysses S. Grant. Her efforts to support the Union resulted in a lifetime of punishment after the war with a loss of her money spent on her efforts, her reduced social standing, and being labeled as a spy, traitor, crazy, eccentric, and mad resulting in a lifetime nickname of “Crazy Bet.”

Van Lew felt she was unfairly labeled as a spy and responded to her critics by saying. “I do not know how they can call me a spy serving my own country within its recognized borders… [for] my loyalty am I now to be branded as a spy—by my own country, for which I was willing to lay down my life? Is that honorable or honest? God knows.”

That did not deter Van Lew and after the war, she was made the Postmaster of Richmond while Grant was president. Van Lew became involved in Republican politics and as postmaster, she helped to modernize the city’s postal system and sponsored a Richmond library for African Americans that opened in 1876. This provided her a platform to advocate for Women Suffrage and Civil Rights. She filled open positions previously held by white men with African Americans and women. In 1883, she was demoted to clerk and was paid less than men in the same position, so she quit her job.

Van Lew died on September 25, 1900, a social pariah. Her inheritance had been spent on her espionage and supporting the family’s former slaves. Upon her death, a group of friends in Boston including the family of Paul Joseph Revere (grandson of Paul Revere), a soldier she had assisted at Henrico County Jail in 1862, paid for her funeral in Shockoe Cemetery in Richmond. The City of Richmond demolished her mansion after her death.

Van Lew who fervently opposed slavery and secession, kept a secret diary buried in her backyard and whose existence would only be revealed on her deathbed. “She is considered the most successful Federal spy of the war,” said William Rasmussen, lead curator at the Virginia Historical Society.

Cited References:

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/elizabeth-van-lew

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/van-lew-elizabeth-l-1818-1900/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/elizabeth-van-lew-an-unlikely-union-spy-158755584/

Additional reading recommendations:

Harper, Judith E., and Elizabeth D. Leonard, Women During the Civil War: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2004.

Van Lew, Elizabeth. A Yankee Spy in Richmond: The Civil War Diary of “Crazy Bet” Van Lew. Edited by David D. Ryan. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1996.

Varon, Elizabeth R. Southern Lady, Yankee Spy: The True Story of Elizabeth Van Lew, a Union Agent in the Heart of the Confederacy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.