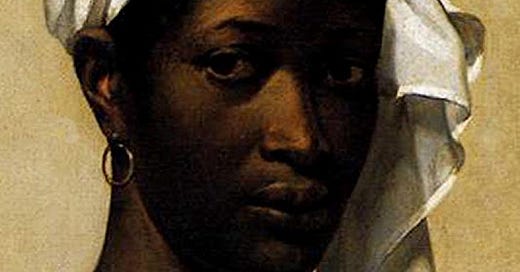

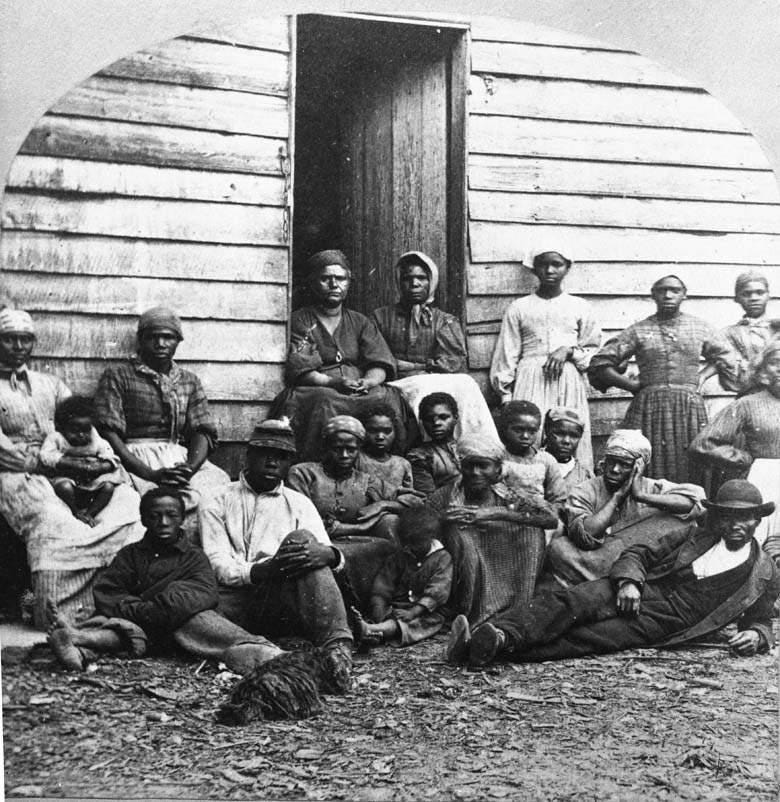

African American women traveled different paths than males in slavery and freedom because of their bodies. They labored in the fields and in their masters’ houses. They were “wife,” mother, and household maintainer and served as “breeders” of new enslaved life for labor or for sale. They were forced concubines or sexual victims of the master, overseer, or any other white man who chose to use her body for his pleasure and her pain. The African American woman was considered all things except human.

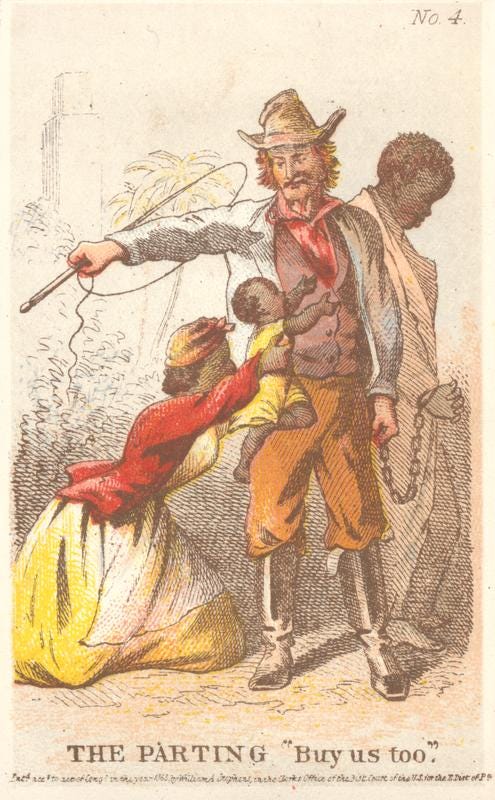

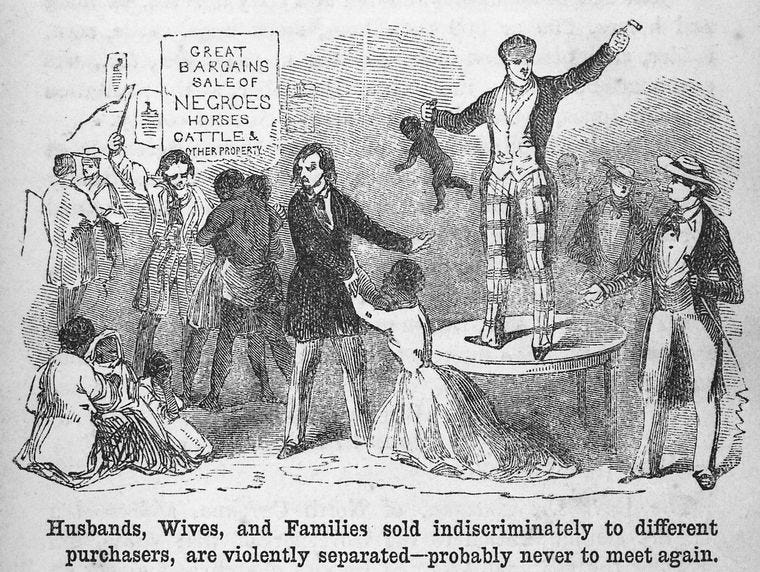

Enslaved African Americans could not enter a legal contract, including a binding marriage. Without marriage certificates, there was no proof of a marriage. African American slaves were viewed as property without legal rights comparable to a farm animal. Slaves as chattel could be processed in a variety of ways that included being bought, sold, transported, mortgaged, attached, leased, inherited, and distributed as gifts. This meant they could not be considered a constituted family. Not only did slaves have no rights of marriage, but they had no parental rights which led to family separation. Enslaved African American women were viewed as “breeders” regardless of their “marriage” status. A slave “marriage” was designated by the term “contubernium” meaning a relationship with no sanctity or civil rights.

Traditional marriage responsibilities could not be fulfilled in a slave marriage. When a husband and wife pledged to protect each other in sickness and health or stay married until death due them part, a marriage with no legal standing or rights of the partners was meaningless. The master’s legal ownership allowed him to control marriages and families as if they were puppets on a very short string. A slave was not able to protect themself or to protect another slave without risking lashes or even death. If the master decided to have his way with an enslaved woman, her husband was unable to defend her without risking his and possibly her life.

Slaveowners forced slave marriages, including second and third “marriages” when a partner had been sold to another plantation. The Savannah River Baptist Association assured whites there was no moral issue with this arrangement. They deemed multiple slave marriages as being "in obedience to their masters.” The white community did not consider the slaves human or civilized.

African American women were often forced into concubinage with their masters and overseers. They were subjected to lashes, physical and sexual abuse, and rape. These arrangements were at the discretion of the master. Polygamy (multiple marriages while still married) were legal for the enslaved and often required by the master when an enslaved woman’s husband had been sold. This assured “breeding” by enslaved women to produce legally enslaved offspring. Their offspring provided the master commodity in labor or cash. Without any legal rights or protection, enslaved African American women were treated as laborers, breeders, and commodities. They were deprived of control of their bodies, the love of a marriage, and the joys of motherhood.

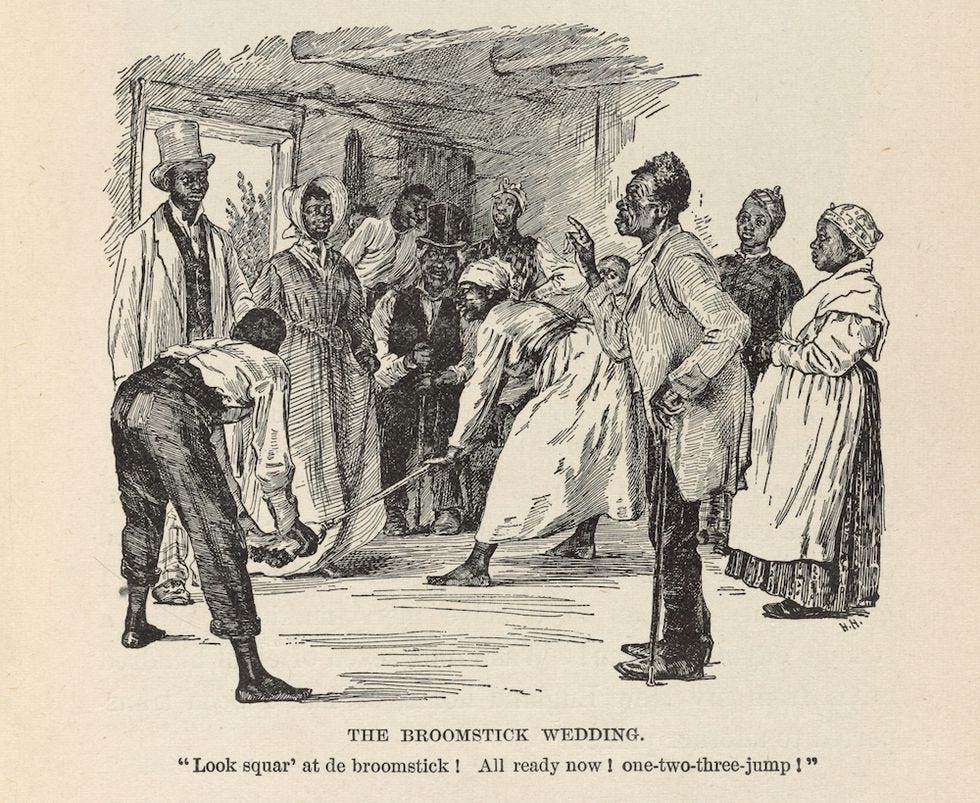

Masters typically arranged courtship and marriage for enslaved women by force or “encouraged” it through social parties known as “frolics.” An Anglo adopted symbolic ritual known as “jumping the broom” proceeded a wedding ceremony that was neither legally nor religiously official. Ceremonial Bibles provided no sanctity of marriage rather they reenforced the idea that enslavement was God’s will. Ceremonies did not include the mention of God nor marriage responsibility.

Other forms of slave marriages included a variety of improvised rituals by the enslaved couple or more likely by their masters. These marriage ceremonies were officiated by a white minister or master or an authorized slave religious leader from a plantation. Jumping the broom was the most common official sign of marriage. Other examples included being married “with a lamp or by carrying a glass of water on their head” or being married by the blanket. One Georgia slave explained this as “We come together in the same cabin: and she brings her blanket and lay it down beside mine; and we gets married that a-way.”

Sometimes the master or overseer would himself “marry” one of his enslaved women knowing there was no legal meaning to the relationship. These relationships could be extremely violent and produce children that the mother had no control of keeping. Sometimes an enslaved woman would try to reject one of these “marriage offers” and face violent consequences.

The enslaved woman’s hardships worsened after marriage. Her pre-marital deprived rights were extended to all aspects of the family union after marriage. Enslaved marriages could include nuclear families on one planation or on different plantations. Marriages could be single parenthood or step-parenthood relationships with a man not personally chosen by the woman. Forced marriages and separations created difficult and traumatizing situations for women. In Antebellum South Carolina alone, approximately one third of enslaved marriages were separated by plantations or even oceans. The marriage union lasted until death or until physically separated by the master.

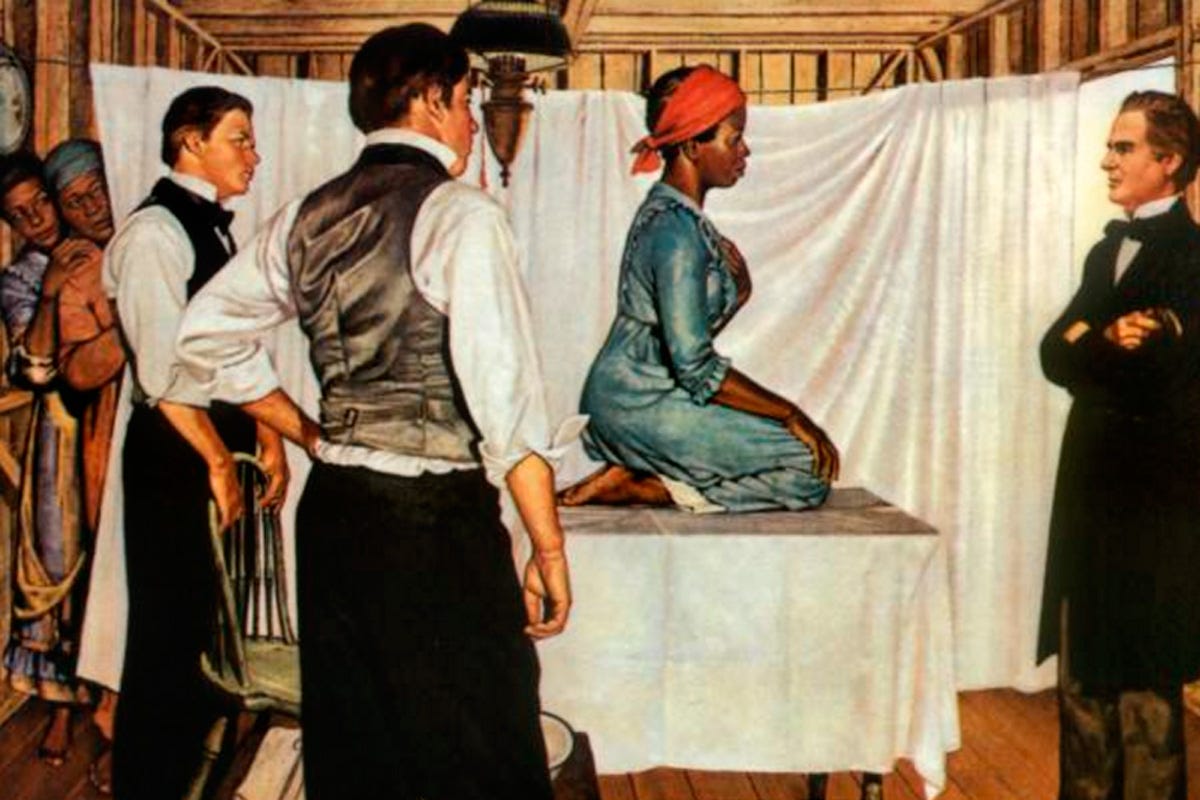

Breeding was the primary concern for the master. The “breeding” of enslaved girls and women ranged from rape to forced marriages. The process of breeding was not only on female slaves. Male slaves were taken as youth based on their physical attributes and matched with the “best” girls to assure the finest of breeding like animals. The health of enslaved women related only to their breeding ability. When there were health issues, the woman was taken to white doctors who exploited them through medical testing to benefit their own personal reputation.

Pregnancy brought no kindness from the master or overseer. Pregnant women worked until they delivered. The masters had ways to physically abuse the mother while still trying to protect the child in her womb. The mother was forced to strip before a whipping, dig a hole in the ground to protect her belly, and lie face down to protect the unborn child while receiving lashings. She was unlikely to be beaten to death because of the value of her unborn child.

A women’s reproductive value was part of the slaveowners’ calculation of her worth. Because of the increased value of a fertile enslaved women, they were the most desirable assets in the marital estate and one of the most fought after possessions in coverture cases.The wealthiest plantation owners divided their properties for gifting to their children based on their slave’s gender. Enslaved laborers went to the sons and young fertile enslaved women went to the daughters.

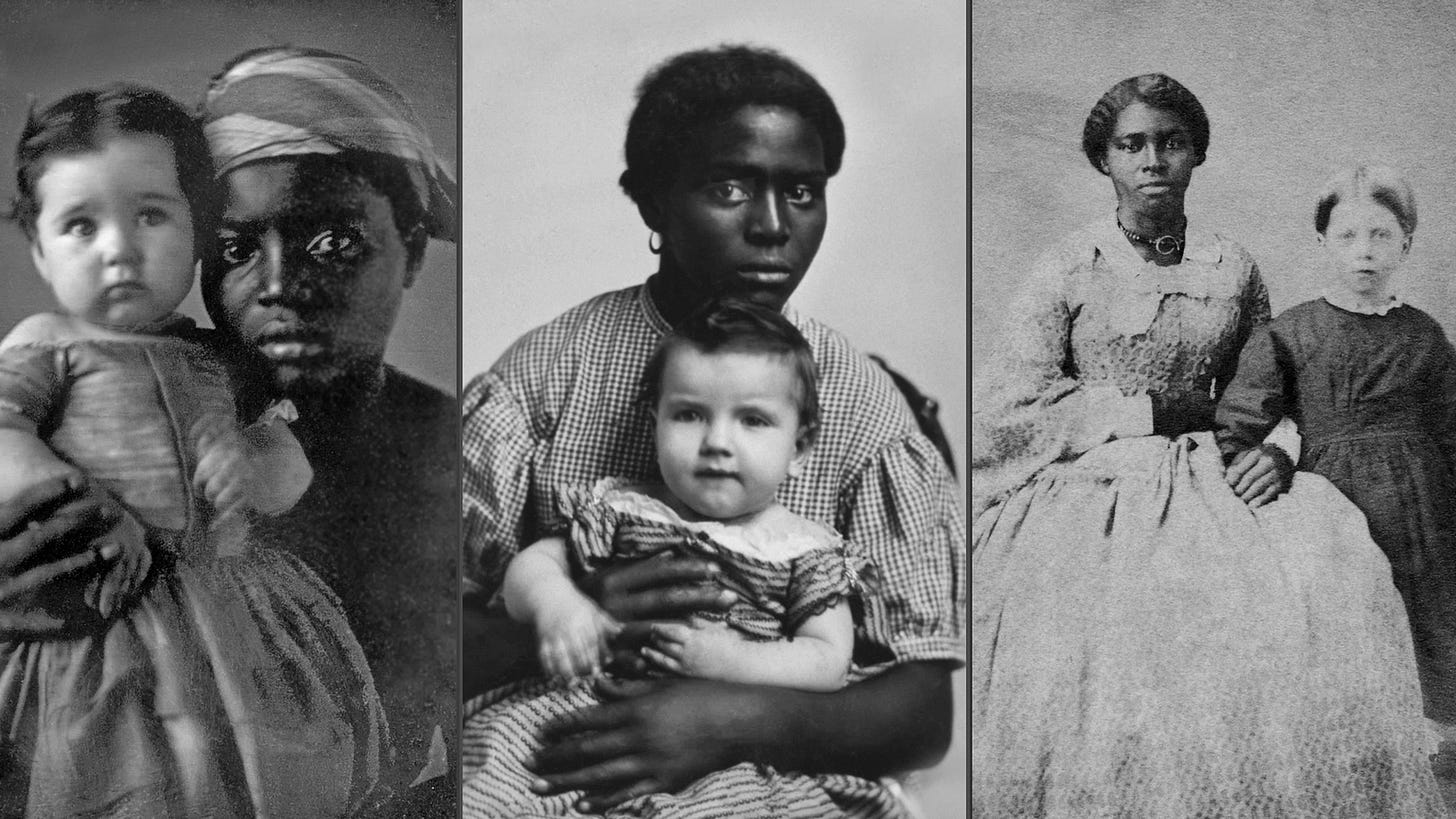

Passes were provided for slave travel between plantations to increase pregnancy potential. A child’s future was independent of their mother’s destiny. Sometimes enslaved babies were kept by the masters while their mothers were sold. If the mother kept her child, she was provided up to a month to recover and then placed back in the field, often with her child on her back. Sometimes the child was sent to the master’s house to be cared for by an enslaved nanny. Motherhood was not physically limited to an enslaved woman’s children. A white mistress might require an enslaved woman to wet nurse her own white child.

Enslaved women juggled childrearing with their chores and had no control over their time or work. Travel passes on the weekend came with a threat of whippings, torture, or death from active slave patrols. Husbands were powerless to protect their wives whether the husband was on the same or different plantation. Laws prevented his ability to protect her or her ability to fight back. Rape was legal and common against enslaved females of all ages regardless of marriage status. No one questioned who fathered enslaved children if they were of mixed race because the resulting pregnancy was attributed to the mother. By arguing Black women were soliciting white men, the rape of the enslaved woman was considered consensual and enticed by the woman.

In the light of Emancipation came the darkness of new laws and trauma. Emancipation required newly freed African Americans to begin an arduous attempt at reuniting families separated under slavery with little or no information or logistical support. Since slave death certificates were not required, it was unclear if missing family members were dead or alive. For husbands and wives, this could be a joyous or complicated reunion based on the possibility of multiple marriages. The legality of marriage after a slave was emancipated met many obstacles in practice. There was a lack of documentation since enslaved marriages were not considered binding.

Past marriages required processes to be recognized. Some southern states amended their constitutions to legalize cohabitating enslaved relationships. Some states provided a six or nine-month grace period for couples to formally “re-marry” by a minister or the court or their relationship would be dissolved. The required filing for a marriage license with the county circuit court by the newly married couples was a prohibitive challenge for many freed people. Failure to comply with filing in these states while continuing to cohabitate made the couple subject to prosecution for crimes such as adultery and fornication. This threat created a flood of requests for legal marriage validation for couples hoping to avoid prosecution and to gain protections awarded through marriage. Federal officials used this marriage verification to determine qualifications of freed African American for citizenship.

Polygamous marriages were not uncommon under enslavement so many African Americans were inherently in violation of marriage laws upon emancipation. This violation impaired the ability for freed African American women to apply for war widow pensions. Not having a marriage certificate to confirm her single marriage or having multiple “marriages,” voided her pension eligibility from the War pension fund if her husband had been killed. Complications at the end of the Civil War were incurred when the first husband would show up expecting to claim his remarried wife. These women were then forced to choose one man as their legal spouse and disavow the other. Punitive state laws were passed that further subjugated these married women. The woman was deemed guilty of infidelity or immorality if she had lived in an "open and notorious adulterous cohabitation” after the death of their husband and before legalized marriages.

Postbellum marriage required the father or husband to be the provider as head of the household and dependents needed to be financially cared for by the parents. Unemployed parents were deemed as paupers and considered of bad character so their children could be placed in servitude to a white person (often their former owner) until they reached the age of majority.

Examination of the era’s state laws defined the lack of rights or control over enslaved African American women’s lives or bodies. Courtships were at the master’s discretion with only one purpose - to produce more enslaved offspring for labor or money. Enslaved marriages were meaningless under the law, in the Church, or by white society. Motherhood provided no parental control of the child’s life and could include nursing white babies. Sexual abuse through violence and rape was legal and rampant. Emancipation in the Postbellum brought more complications on the status of marriage, the rights of marriage, and the subjugation of African American women to Black men in addition to white men. The enslaved African American women’s body is an important component of her history.

References

Katherine M. Franke, Becoming a Citizen, 283 (Act of Mar. 9, 1866, tit. 31, § 5, 1866 Ga. Laws 240)

William Goodell, The American Slave Code in Theory and Practice: Its Distinctive Features Shown by its Statues, judicial decisions, and illustrative facts. New York, American and foreign anti-slavery society, 1853. Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/11008422/.

Herbert George Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925 (New York, N.Y: Vintage Books, 1993).

Michael Grossberg, Governing the Hearth: Law and the Family in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

Darlene Clark Hine, Wilma King, and Linda Reed. “From Three Fifths to Zero” in We Specialize in the Wholly Impossible: A Reader in Black Women’s History. Brooklyn, NY: Carlson Pub., 1995.

Tera W. Hunter, Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press, 2019).

Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

George McDowell Stroud, A Sketch of the Laws Relating to Slavery in the Several States of the United States of America. United States: Kimber and Sharpless, 1827.

Emily West, Hidden Voices: Enslaved Women in the Lowcountry and U.S. South, Lowcountry Digital History Initiative,” 2020. https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/hidden-voices.

Deborah G. White, Ar’n’T I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999).