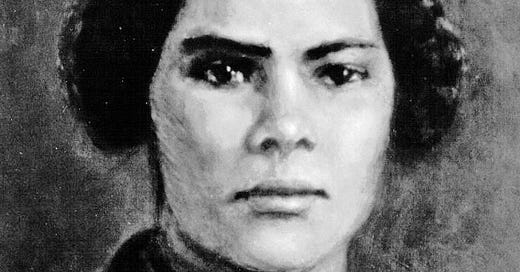

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893)

19th century feminist, suffragist, lawyer, and first African American woman newspaper editor

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823–1893) is recognized as the first United States (U.S.) Black female news editor. She used her platform to speak out against racism, sexism, and violence against women. Born to abolitionist parents in Delaware, Shadd established herself in a male dominated industry during the 1850s. Her feminist motto was “Self-reliance is the true road to independence.” Shadd entered the world with more privileges than most of her peer group, born into a politically active family and the oldest of thirteen children. Her father was a delegate to the Conventions of Free People of Color and the annual convention president in 1833. Her family had a successful shoe store, and their home was part of the Underground Railroad. After six years of a primary education, Shadd attended a Quaker school where one of her teachers was a delegate to the 1838 Anti-Slavery Convention of American women. She herself became a teacher at the age of sixteen.

Shadd was an intellectual revolutionary who was born years ahead of her time. She argued during her lifetime that race was a social construct to advance societal hierarchies and not a biological identification. She refused to use racial terms to describe Blacks - instead referring to African Americans in terms of their “complexional character.” Shadd believed by eliminating the social constructs of race, you can eliminate the discriminatory labels attached to them. This could also be applied in the legal system and would remove all discrimination under the law.

A journalist who met Shadd in the 1840s described her as physically tall, attractive, and feminine but one who could carry an air of confidence that whites called “saucy.” He describes an incident where Shadd entered a stagecoach reserved for whites and with an impressive wave of her hand, commanded the driver (who would normally deny people of color a ride) to take her to her destination and bewildered, the driver took her there.

In 1849, Shadd established her core beliefs in a letter sent to Frederick Douglass which he published in the March 23, 1849, issue of his North Star newspaper. The letter detailed Shadd’s comments on the terrible living conditions for Blacks in New York in response to a piece published by Minister Henry Highland Garnet. Her recommendations in New York and across the nation regarded the uplifting of African Americans. She stated this rising up could happen by, “…not waiting for the whites of the country to do so” for them and continued “we should do more and talk less.” She specifically recommended becoming producers rather than consumers and looked towards developing more farming interests.

Living in New York when the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 passed, Shadd led her family to Canada which was a welcoming haven for free Black refugees. Fifteen thousand Blacks emigrated to Canada where they were able to buy land, be educated, and vote. Once in Canada, Shadd opened a school for Black refugees in Windsor, across the border from Detroit. She wrote to the American Missionary Association (AMA) requesting financial help and received only half of what she requested. Once the school was operational, it served 56 children and adults ranging in age from four to forty-five years old.

At the time, there was a competing narrative about whether Blacks should stay in the States and fight for abolitionism led by Frederick Douglass or emigrate to Canada. Shadd encouraged emigration but realized there were those in the movement who would exploit new refugees for their own profiting. Among these people were Henry and Mary Bibbs who ran the Refugee Home Society. In letters to the AMA, she accused the Bibbs of lining their own pockets with funds meant for the refugees. The Bibbs responded by gathering white allies in New York and slandering Shadd in the Voice newspaper. Soon after this incident, Shadd’s relationship with the AMA was terminated due to her “evangelical sentiments.” This fallout led to Shadd launching her own Black newspaper called the Provincial Freeman in 1854. While it listed a prominent Black minister as the editor, Shadd served as the editor, business manager, writer, and all other titles.

Shadd’s publication became the first woman edited paper in North America and was an equal opportunity paper offering support and criticisms of both Blacks and whites. Shadd’s sample editorial shots targeted a racist white editor and those who subscribed to her paper without paying. William Still notes in his book, “The Underground Railroad” (1872), that her travels throughout the area were difficult as she faced the nature’s elements and discrimination.

Shadd was outspoken on many issues and shied away from few difficult topics, including the rape of Black women. She provided an accounting of an attempted rape of a Black school teacher by J.F. Grady, an Irish dentist. The woman had gone for treatment of a tooth extraction when the dentist locked the door, cornered her, and attempted to assault the woman. Threatening to scream and then to break a window, the victim was able to secure her release and then went public in Shadd’s newspaper with her accusation. The dentist had tried to leave town but was caught, charged, and convicted of assault and required to pay court fees and a fine.

This wasn’t the only time Shadd addressed the sexual exploitation of African American women in her newspaper. In 1855, she covered a story that what most likely presented in another paper concerning an enslaved Missouri woman named Celia. The narrative explains Celia had suffered years of sexual abuse by her owner, Robert Newsom. The trial records detail the abuse accusation for years and that the man fathered her second child. Celia had pleaded with the white family to stop the abuse, or she would be forced to hurt him. On his last visit to assault her, she begged him to leave her alone because she was sick, but he continued with his intentions anyway. Trying to only hurt him, she struck Newsom twice in the head with a stick and accidentally killed him. Celia then proceeded to burn his body in the fireplace. She swept up the ashes and dumped them on the side of her path to the stables. Celia tried to claim her body as hers, but the court only recognized her body as property. They denied the laws her lawyer offered on the right to self-defense. Without doubting Celia’s story, her confession was without rights and the county judge refused to have the jury hear from her defense lawyers. An appeals court agreed with the judge and a few months after the trial, Celia was sentence to death and hung.

Shadd’s feminist views were printed in her newspaper, The Provincial Freeman. Together with her sister, Amelia Shadd, they published stories and editorials about women fighting slavery and gender discrimination. They encouraged women to pursue whatever made them happy and to express themselves by submitting their written viewpoints to publications. They covered feminist movement meetings and highlighted the work of Lucy Stone’s speech in Toronto in 1854. Shadd lamented the fact that more Black women were not in attendance at this meeting. After the meeting, The Freeman benefited from generous donations from feminist Lucretia Mott.

The Freeman also wrote a feature of Sojourner Truth, the more prominent African American activist at the time. The piece highlighted Truth mocking white Americans as comingling abolitionism with racism. Like Truth, Shadd did not believe in excusing complicity that held back Black progress. This interaction is believed to be the only one between these women and one that Shadd claims was unforgettable for her.

In 1855, Shadd was granted permission to speak at Frederick Douglass’s Colored National Convention on the benefits of emigrating to Canada. The debate to allow Shadd to speak was divided with a final vote of 38 to 23 allowing her to present. Originally allowed to speak for ten minutes, she spoke for twenty minutes at which point the meeting was out of time. One attendee wrote that even though he disagreed with Shadd’s idea of emigration, she gave a convincing and passionate speech that enthusiastically captured the audience’s attention and gave them something to think about. However, after the convention, Shadd blasted her hosts and wrote in her newspaper that the convention “was quite a disorderly body and broke up without doing a great deal.”

While in Philadelphia for the convention, she participated in a formal debate on Black emigration against an accomplished debater who promised to treat her the same as any male opponent...by the end of the debate, Shadd was declared the winner. Unfortunately, her assertiveness as a Black person and as a female alienated her to both whites and Blacks and impacted her ability to raise funds. She took aim at these people in her paper and wrote, “Better far to have a class of sensible industrious wood-sawyers, than of conceited poverty-starved lawyers, superficial professors, or conceited quacks.” After the editorial was published, she relinquished the reins of the paper to a Black male minister and said her goodbyes so the paper could continue its work. However, a year later, she was again on the masthead with the addition of Isaac D. Shadd and H. Ford Douglass.

In 1855, Shadd married Thomas F. Cary, a man 12 years her senior with three kids who owned a barber shop and bathhouse. He took care of the children and household while she traveled for work. Her husband died after a long illness in 1860 leaving Shadd-Cary with three children and without income so she returned to teaching, writing, and editing.

After the passage of the Conscription Act for soldiers to fight for the Union, Black recruits were needed from the States and Canada to fill the ranks. M.R. Delany, the first Black man commissioned as a U.S. Army major, contacted Shadd-Cary seeking her support as a paid recruiter. Shadd-Cary became the only women hired as an official military recruiter. Her recruits were considered the finest men and were sent to represent Boston and Connecticut.

In 1869, Shadd-Cary went to Washington to join the Universal Franchise Association, the first women’s suffrage group in the nation’s capital. Shadd-Cary represented the group at the Colored National Labor Union, a predominately male organization in 1878 where she spoke about women’s rights and workplace issues. She was made the chairwoman of their Committee on Female Suffrage and became the only woman elected to the Union’s executive committee.

Mary Ann Shadd-Cary taught school and wrote for Black newspapers after the Civil War. At the age of 46, she attended the new Howard University Law School as the first female student. She studied at night while teaching in Washington during the day. Although listed in the inaugural class of 1871-1872, the district’s legal codes prevented women from being admitted to the bar creating an obstacle to her career. Shadd-Cary charged sex discrimination and left her studies. After incurring financial difficulties for many years, she returned and completed her studies in 1884 at the age of sixty.

In 1871, Shadd-Cary joined a dozen women and approached the District of Columbia’s Board of Registration to petition for the right to be added to the voter rolls. She was one of three Black women in the group. Frederick Douglass appeared to provide his support for the effort. The Board allowed each woman to present their case only to deny them the right to vote. A legal case was then filed that challenged the decision under the Constitution. The case was lost on the grounds that Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendment do not guarantee political rights.

Shadd-Cary later argued before the House Judiciary Committee in 1872 on behalf of Black women’s suffrage. She applied the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to her argument stating that it clearly applied to Black women as well as Black men which became known as the “new departure.” However, noting her audience, she applied the argument to the broader base that all women should have the right to vote, otherwise, women were only nominally free without a political voice. She recommended that the Constitutional Amendments strike out the word “male.” She argued unsuccessfully that if women are taxpayers, they should also have representation. By arguing that the Constitution should be gender neutral, it broadened the intent of the Black feminist movement to be more inclusive of white women.

Shadd-Cary continued her Black women’s suffrage fight and in 1876, she wrote to the National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA) and requested the inclusion of ninety-four African American women’s names in their July 4th centennial autograph book as signers of the Women’s Declaration of Sentiments. The letter was acknowledged but her request was denied leaving these voices unrecorded. In an attempt to be heard, Cary unsuccessfully offered the votes of African American women to either the Republican or Democratic Party, if either party would champion their right to vote.

Committed to both the labor and suffrage causes for Black women, Shadd-Cary was viewed as a radical in her approach. In 1880, she addressed a Black congregation in Washington and told the audience to “obtain the ballot and look alive after the welfare of both girls and boys in the training of the youth, working promptly to extend the number of occupations for women.” Her demands presented to the congregants included equal rights, equal economic opportunities, training programs for male and female youth, the establishment of a Black feminist newspaper, and advisory councils on land ownership and business management. She also recommended a joint stock company controlled by women. Shadd-Cary combined economic, political, and educational rights in her revolutionary presentation placing her significantly ahead of her time as an African American and female activist.

References

Jones, Martha S. Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2021.

Peterson, Carla L. Doers of the Word: African-American Women Speakers and Writers in the North (1830-1880). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Sterling, Dorothy. We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1997.

Sterling, Dorothy. Speak out in Thunder Tones: Letters and Other Writings by Black Northerners, 1787-1865. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, 1998.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920. Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1999.